I can think of at least a few buildings in the world that exquisite enough that they warrant a little elbow room. The Taj Mahal comes to mind. The Farnsworth House. Certain monasteries and castles. Most quotidian pieces of architecture, though, gain their value not from splendid isolation but rather from their relationships -- with surrounding buildings and streetscapes.

Setbacks, which are perhaps the most ubiquitous way that planning imposes on architecture, are to these relationship what adultery is to romantic relationships.

For those residents of, say, Paris, Vienna, and New York City who are unfamiliar with setbacks: they are spaces that “set” buildings “back” a certain distance from the property line and, usually, the sidewalk. A distant but useless cousin of the front yard, they appear in, I reckon, the majority properties developed nationwide since 1950 and nearly all properties developed in California.

For all their popularity, setbacks have little basis in engineering or architecture. They are simply regulatory whims.

Setback requirements come in all shapes and sizes. Some are minimal (a foot or two) while others are dramatic (ten feet, fifteen feet). Some make way for pleasant things like outdoor dining spaces; others turn into unwelcoming bollards. In each case, setbacks are mandated voids, either to be ignored or landscaped, unusually in decidedly half-assed ways. Ferns for everyone!

(I refer mainly to setbacks that separate buildings from sidewalks, not to those that separate buildings from each other. I have slightly more sympathy for the latter type.)

Received wisdom holds that setbacks make urban spaces feel less crowded. They supposedly ensure that buildings do not overshadow streets and sidewalks. They create the illusion of less density and protect buildings’ personal space. They create room for “green space,” “light,” and “park-like settings,” which sound great in real estate listings. They assume that buildings are impositions on their cityscapes, to be contained so as not to offend delicate sensibilities.

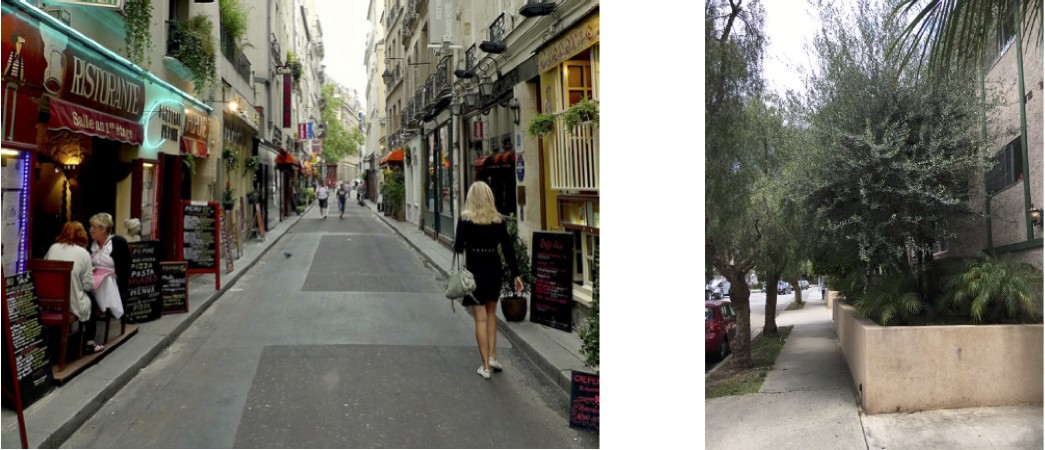

|

| A street in Paris (l.) and a street in Los Angeles (r.). |

This rationale is mostly nonsense, of course. Like so many other concoctions that come courtesy of regulators rather than designers, setbacks are a scourge on our cities. At best, setbacks persist because of habit. But, like elevator music and parsley, they are not actually as pleasant as we pretend they are. They confer psychological satisfaction even if they have nothing to do with aesthetics or economics.

To the proponents of setbacks, a few patches of grass might as well be Luxembourg Gardens. But think about the classic street in any of the cities I cited above. If you enjoy Paris or New York, you already know why you shouldn’t like setbacks. Density in a city is good. And not just population density. The actual appearance of density (which may or may not have anything to do with population density, depending on the type of structure in question) is good, too.

With scant exceptions, the most pleasant streets and neighborhoods – from the Île de Saint Louis to Greenwich Village to Old Town Tucson to the row house neighborhoods of Philadelphia – are those not where buildings recede from their streets but indeed where they are closest together, working in harmony with streets to create a public realm. A sense of enclosure is one of the hallmarks of great streets, whereby space is created and defined by the intersection of vertical and horizontal planes. Pedestrians also benefit from the shade created by snug buildings and vertical facades (and awnings, if they’re lucky). The no-man’s-lands created by setbacks detract from streets and buildings alike, only scarcely less aggressively than do walls and cyclone fences.

From a developer’s perspective, setbacks waste space and, therefore, money. Who would want to give precious square footage to ferns, ficuses, and snails rather than to people? Even worse, setbacks create lousy buildings. When a pedestrian’s feet and eyes might travel mere inches from a façade, that façade ought to be at least somewhat attractive or inviting. Setbacks invite architects to pay that much less attention to detail. I enjoy dragging my fingers on a Parisian façade because, well, Parisian facades are attractive.

To fans of setbacks, a building nestled right up against a sidewalk is scary. A ten-foot “landscaped” setback? Just fine. Never mind those shrubs look like mighty attractive hiding places to aspiring muggers. There’s a reason it’s “eyes on the street,” not “eyes on the setback.”

What about privacy? I’m sorry, but if your living room faces the street, you’re going to need curtains no matter how far back you are. Setbacks don’t create privacy. They create the illusion of privacy.

In short, there is no economic, aesthetic, or security reason for setbacks to exist. Cities have gotten along fine for centuries without them. So, what gives?

Let’s think about who might lobby for setbacks, either in an individual project or in a zoning code. They’re certainly not the tenants of buildings. Unbuilt buildings have no tenants. The people most likely to demand that a development be worse are those who don’t like development in the first place and who object to density on principle.

Setbacks are the currency of anti-development activism. Homeowners who like their cities and their property values just fine don’t care how far away a building is from a street. They’re likely only to see those buildings at 35 miles per hour anyway, and probably from a lane or two away (plus a few feet if there’s a devil strip). But they know how to push planners around.

For them, setbacks are just a bargaining chip – a palpable way to stick it to developers. Setbacks persist because they are quantifiable and negotiable. Once opponents have whittled down the number of units or the amount of floor space in a project, they can bring on the setbacks. The developer wants a setback of zero feet. Neighbors want a setback of ten feet. When it gets settled at five feet, the neighbors chalk up a win.

Why is that a win? Because they don’t care in the first place. They gain nothing, except for a five-foot pain-in-the-ass for the developer and a lousy place to take a stroll. This isn’t advocacy, and it’s certainly not planning. This is urban trolling.

I bemoan setbacks not to redesign every condo building from Riverside to Santa Monica. Setback regulations and their proponents have already done their damage to the buildings that exist and the streets that they face. Fortunately, with a few deletions from zoning codes, and more tenacity from the planners who care about density, walkabilty, aesthetics, and fairness, cities can play with a full deck once again.

And when the next Shah Jahan comes along with a great idea for a mausoleum, then we can talk.

Photo Credits: Paris: Zoetnet via Flickr; L.A.: CP&DR Staff.