A working-class neighborhood north of downtown L.A. is slated for a development project unlike any other previously built in the state: A combination of housing and a public school on a shared site. Set to start construction this winter, the Glassell Park project is being built jointly by Los Angeles Unified School District and Abode Communities, the nonprofit homebuilder formerly known as Los Angeles Design Center.

Joint use is an awkward name for an attractive concept. Two or more public agencies – schools, libraries, child-care centers, clinics – put their money together to build a single project that serves several purposes. This method of combining the resources of two underfunded departments can solve problems for both parties, such as inadequate resources id any single agency to build a project by itself.

The novel combination of a public agency and a private developer makes Glassell Park even more innovative still. In this case, Los Angeles Unified and Abode are sharing a small, 1.4-acre block that until recently served as surface parking for an elementary school across the street. The south side of the block will contain the Glassell Park Early Education Center, devoted to kindergarten and pre-K children. (The existing elementary school remains across the street from the project.)

On the north side of the block is a four-story, 50-unit apartment building, made up entirely of two- and three-story units appropriate for families. All the units are intended for low- or moderate-income households, in this case, families earning 30% to 60% of median income in Los Angeles County.

The Glassell Park Early Education Center (left) is proposed for the southern strip of the 1.4-acre site (seen from above at right).

Beneath the block are two levels of underground parking, which replaces the parking for the elementary school while providing spaces for both teachers and residents. The underground parking would be impossible without joint use. And without the subterranean parking, the project itself would have been impossible, because much of the buildable area would be eaten up by surface parking.

The master plan by Goodale-Gonzalez, which also designed the buildings, has made the two buildings as different as possible. The school is an L-shaped building that hugs the sidewalk with a row of single-story buildings that looks outward to the public realm. The apartment slab, on the other hand, looks inward to maximize privacy on a block surrounded by streets on three sides.

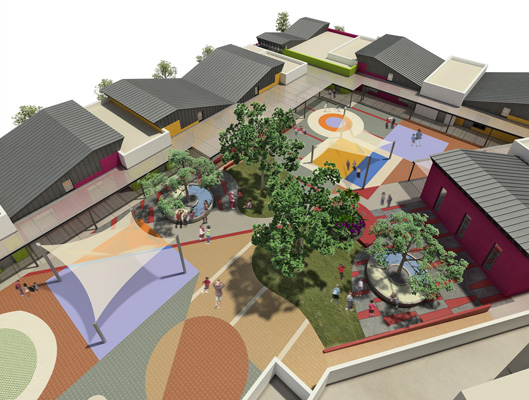

In between the buildings is a 10,000-square-foot "outdoor learning classroom," which provides outdoor space for young children. During non-school hours, the playground can be opened for the use of apartment residents. Again, this generous amount of active open space, typically lacking in most affordable housing projects because of cost, is made possible by the joint-use model.

Although Abode Communities has not built housing on a school campus before, it has built several child-care centers, and these experiences have taught Abode how to secure areas intended for young children, according to Robin Hughes, Abode president and chief executive.

"From a physical design standpoint, there is always a need to separate public and private uses on the same site, and this is one of the things we do well," she said. Both the school and the apartments have separate street entrances, and even the parking has separate entrances.

Abode won the project through a request for proposals process initiated by the school district. The combined school-and-housing development was approved by the Los Angeles Planning Commission in April.

The playground area of the project (left) and the northwest corner of the apartment block (right). (Images courtesey of Goodale-Gonzalez Architects.)

As with most low-income housing projects, the financing for the Glassell Park project is complex (I still can't get used to the idea that financing a few dozen units of affordable housing is far more difficult than funding a giant shopping center). The $27 million package consists of a $2.3 million mortgage from US Bank; $2.6 million from the Los Angeles Housing Department, a $2.6 million Proposition 1C infill grant, and $11.7 in general partner equity. As mentioned above, Los Angeles Unified is a big underwriter, providing $2.9 million in a ground lease note and another $4.1 million equity contribution. The school district contribution covers the cost of the underground parking, to be shared by the early education center, the nearby elementary school and apartment residents.

The federal stimulus bill also makes an appearance, in the form of $1.3 million funneled through the California Tax Credit Allocation Committee. These funds supplement the value of low-income housing tax credits, which are sold to investors and are an important source of cash for below-market projects. The recession has driven down the market value of the credits; the stimulus is providing up to 12 cents on the dollar above the price the investors pay for the credits so projects can meet their budgets.

In return, the Glassell Park housing development must pay rent to the school district for its 66-year ground lease; these payments vary with the income generated by the housing and will likely range between $10,000 and $15,000 yearly.

When I first began writing this column 20 years ago (!), I tried to guess whether certain innovative projects could serve as prototypes. While there is always danger in such pronouncements, the Glassell Park concept definitely has legs. Combining schools and housing is a winner, especially in communities where public resources have dwindled to a trickle.

The concept of monetizing surplus school land is a long-established doctrine in the state, even if few projects have been able to realize it. Glassell Park is a modest project that leverages the resources of the school district to make a superior environment for both school and apartment dwellers. Ms. Hughes of Abode Communities says her firm is already under contract with L.A. Unified for a second project of the same type. The awkward name of joint use has begun to sound like music.