Last week I published a short op-ed in the Los Angeles Times suggesting that low-density development patterns are one of the reasons California cities are experiencing fiscal problems. But I have to admit I wasn't prepared for the type of pushback I got from readers, most of whom seemed to view me as an apologist for public employee unions or as a radical wishing to overturn Proposition 13.

I tried to be careful about how I made my case–acknowledging that public employee pensions are a huge issue no matter what and also acknowledging that Stockton, in particular, made their problems worse with grandiose urban redevelopment projects.

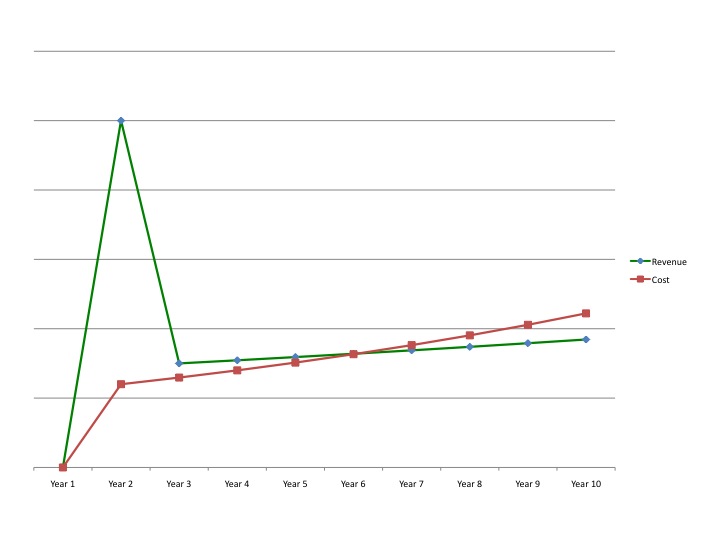

I made a particular point of the fact that, under Proposition 13, the buying power a city gets from a new development project declines over time, especially in relation to the cost of servicing the project. I borrowed this point from a talk I once saw given by Mike Multari, the former San Luis Obispo city planning director and longtime partner in Crawford Multari & Clark. Mike used to draw a chart depicting the revenue-cost curve of a typical development project over time, showing that eventually there's a crossover where the project runs a deficit. (I've replicated The Multari Curve crudely here.)

Mike's point was that most of a development project's revenue bump comes at the beginning, with impact fees and a big increase in property tax, but the impact fees go away and after that property tax increases slowly because property isn't reassessed unless it is sold. His point was that the only way to cover the gap was to keep approving new projects and get a new "hit" of revenue. And it all comes crashing down when the new projects stop coming. Which is what happened in 2008.

I guess I expected that some people wouldn't believe all this and suggest, instead, that sprawling development projects do make money for cities. Naively, I didn't expect anything else.

The blowback to the piece came in several waves. First were the online comments posted underneath the piece itself. My article was called everything from "baloney" to "fatuous nonsense" to "commie propaganda." Several people pointed to sprawling, non-union Texas as proof that I am wrong, as cities there are doing fine compared to cities in California (which, by the way, isn't true). Substantively, most of the comments were variations on the following themes:

1. I'm an apologist for public employee unions claiming that pensions aren't a problem.

2. I'm trying to divert attention from my own dismal record as a tax-and-spend liberal on the Ventura City Council.

3. I'm one of those crazy people who think Proposition 13 should be repealed.

None of which I said or meant to imply in the article.

Then came my appearance on Larry Mantle's normally thoughtful Air Talk show on KPCC. In the interest of balanced journalism, Larry recruited anti-anti-sprawl economist Wendell Cox to refute me. I like Wendell personally, but I don't care much for his research; in fact, I have devoted considerable effort on CP&DR blog space to tearing it apart.

Wendell predictably argued that I was wrong but then, as he typically does, blamed everything on restrictive land-use regulation. I agreed with him that land-use regulations are often too restrictive and lock in large-lot zoning where it is unnecessary. Then at the very end of the show Wendell circled back to attack SB 375 and the horrors of 30-unit-per-acre zoning (imagine!). I wanted to reply by saying the market's going in that direction anyway – something Wendell and the other pro-sprawl economists stubbornly refuse to believe -- but Larry was pressed for time.

Subsequently Wendell emailed me in very gentlemanly fashion, so I asked him if he agreed that the market was changing. He said that trying to predict the housing market today would be like trying to predict it in 1931 – his way of saying that the economic downturn has so skewed the market that you can't tell how it will turn out in the end. Sometimes I wonder whether these pro-sprawl guys have any Millenial kids. And what does all that have to do with the question of whether sprawl costs money?

Then came the L.A. Times letters. As it turns out, nowadays not only does the L.A. Times publish online comments and letters in the paper but they have a whole separate online section called Postscript, in which the author gets to respond to a letter-writer. They gave me two choices, and I chose to respond to Sidney Anderson of Mission Viejo, who said I was only half-hearted in my criticism of pensions and also claimed that I was in favor of repealing Proposition 13, which he claimed had saved his house. "Prop 13 and Sprawl. Sure." I responded by saying I actually agree with Mr. Anderson on pension reform and that smart growth can help balance a city's budget within the constraints of Proposition 13.

But even this wasn't the end of it, because both the interchange with Sidney Anderson and several other letters appeared on the Times web site and in the newspaper, generating even more comments, which – for better or worse – I responded to, thus getting into the weeds of how cities are hemmed in by state pension laws. Which is not exactly where I expected to end up.

I'm happy that the piece attracted so much attention and comment. I don't expect people to accept everything I say, but I didn't expect all the curves I've gotten in the last week. But one thing I have learned: A picture really is worth a thousand words. So in the future, in order to make my point, I'm just going to draw The Multari Curve.