At some point when you’re reading this piece you’re going to say to yourself, “What about the Eiffel Tower?!”

I’ll get to that. First, let’s talk about San Jose.

Over 1 million people live in San Jose. It’s the tenth-largest city in the United States and the home of the richest industry western civilization has ever known. It’s also basically an enormous suburb. Its aesthetic varies between generic suburbia and generic office parks, some of which are laughably unattractive, especially considering the rents they command. San Jose’s 180 square miles have less character than do single city blocks in nearby San Francisco or Oakland (the latter of which outgrew its “there’s no there there” derision long ago).

Maybe I’m being harsh, but I don’t think I’m saying anything that residents and businesses in San Jose aren’t already aware of. It’s the anti-San Francisco, and it has quietly, and impressively, developed according to the norms of its time and place.

Recently, though, a group called the San Jose Light Tower Corp. proposed the erection of a landmark tower—a yet-to-be-designed $150 million beacon, of indeterminate height, that would advertise San Jose to its neighbors and the world. It would, in the words of its promoters, be a “powerful and enduring icon will be the place every visitor must see when coming to Silicon Valley.” This enormity was borne out of the idea that a major world city—which San Jose is, at least economically—needs to be more recognizable and that the tech industry needs to be celebrated, as if it has any trouble celebrating itself already. Bits, bytes, and stock options are all well and good, but you can’t gaze up at them in awe.

I happen to think that this plan has about as much chance of getting built as MySpace does of making a comeback. But it’s still worthy of discussion. Even as a thought experiment, it can help us think about what we should build and not build.

The tower proposal represents all that is wrong with urbanism today. I use “today” loosely, since the idea owes itself more to the 20th century sprawl mentality than to current planning trends. But that mentality dies hard. I don’t know what $150 million buys you these days. But, whatever the cost and however high it might reach, the tower wouldn't solve any of San Jose’s actual problems. It wouldn't make it less sprawling. It wouldn't make its neighborhoods more walkable or its boulevards any less massive. It wouldn't make it easier to get around or more pleasant. It wouldn’t reduce the gap between poverty and ultra-wealth. It just would just make San Jose more noticeable—in the most superficial way possible.

The San Jose tower falls into the all-too-common trap of mistaking a skyline for a city. As I wrote recently in Common Edge, skylines are discrete and identifiable and therefore appealing. They are convenient signifiers to put on postcards or in the backdrop of local newscasts. They are images that, in many cases, have come to be synonymous with their respective cities.

The problem is, as much as we might like to gasp at downtown skyscrapers (or, in the case of San Jose, squat corporate superblocks), no one lives in a skyline. They have little to do with the daily, human-scale experience of a city. They reveal nothing about a city's character, economy, or culture. Take a look at San Jose's skyline and, say, Little Rock's and see if you can tell what it's like to live, love, work, and commune in either place.

A monumental tower pretends that a soaring, bootless structure will, instantly, make San Jose a city worthy of attention. If only it was that easy. I submit that, however much attention a tower would garner, it will most certainly not make San Jose a better city. It will, in fact, distract San Jose from the process of improving itself.

|

San Jose already has plenty of things going for it. Urbanism is not one of them. What San Jose needs to do with its wealth and status is not advertise that wealth and status but rather invest it in the types of design, infrastructure, and private and public developments that will make it more urban and break it out of its Vietnam Era mold. Like many other postwar American cities, regardless of whether or not they are considering odd PR stunts, San Jose can and must reinvent itself. The proposed competition to design the tower would be a bonanza for architects. But so would commissions to update San Jose’s sidewalks, street furniture, signage, mobility patterns, and urban design guidelines. San Jose must figure out how to promote density, intrigue, and interaction. It must develop the sort of dense, multi-use streetscapes that characterize truly great cities.

I am, of course, essentially describing San Francisco. Must San Jose emulate San Francisco? That wouldn’t be a bad thing. Then again, maybe San Jose can put its wealth and brainpower to the task of coming up with new, dare I say innovative, approaches to 21st century urbanism. San Jose should figure out how to retrofit itself, creating a denser, more pleasant 2.0 rather than just sticking a weird piece of new hardware a city whose layout shares more in common with vacuum tubes than touch screens. If it’s smart about it, Google might actually pull this off with its forthcoming mixed-use village in downtown San Jose. Surely other civic boosters can do the same.

Back to Paris.

I know. Everyone hatedhatedhated the Eiffel Tower when it was built. And look at it now: it’s one of the most famous, beloved structures in the world, symbolizing one of the most famous, beloved cities in the world.

The Eiffel Tower is the exception that proves the rule.

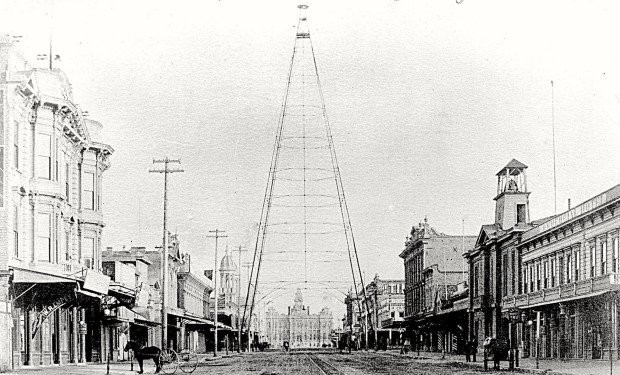

Paris already was a lovely, dense, horizontal city before the tower. It already had the grandeur of the Champs Elysees, the romance of the Marais, the history of the Ille de la Cite, the bold interventions of Hausmann, and cafe after cafe after cafe. Paris didn’t need a tower to advertise itself. Eiffel was lucky that Paris allowed it to be built. Its genius derives from the contrast between the tower’s verticality, modernism, and engineering skill and the city’s preexisting charm, history, and scale. (Oddly, the “Light Tower Corporation” is named after a 237-foot tall 1880s structure that stood in San Jose which, the company’s website claims, inspired Gustav Eiffel.)

|

| The original, 1880s-era San Jose Electric Light Tower. |

I could say much the same for New York before the Empire State Building, St. Louis before the arch, Chicago before the Sears Tower, and, yes, San Francisco before the Transamerica Pyramid. Meanwhile, look no further than the plodding, overtall Salesforce Tower for a cautionary tale. It dominates the San Francisco skyline like its namesake dominates customer relationship management. As John Branch asked recently in the New York Times, "Will the San Francisco skyline ever be as beautiful as it was before the Salesforce Tower rose like a middle finger to the city’s low-slung aesthetic…?”

I reckon it won't.

San Jose would also do well to consider California's ultimate midair bauble. Fittingly enough for a city that trades on image and fakery, Los Angeles’s most famous structure isn’t even as substantial as a tower. It’s a meaningless, two-dimensional advertisement that has, somehow, remained beloved even as the city became scarred over the decades by freeways, dingbats, mini-malls, and Angelyne billboards. I’m not immune to the charms of the Hollywood Sign. I’ve hiked near it and I get a thrill when I view it from the 10 Freeway, knowing that I’m looking upon a landmark that has inspired so many dreams of stardom. But a sign doesn’t put a roof over anyone’s head.

I don’t oppose monuments, and I’m not against fun. But I’m against eating cake before you’ve had your peas and potatoes. I’m against displays of wealth that loom over people who struggle to pay rent. San Jose, like almost every other California city, has a lot of work to do -- especially as housing prices rise, congestion worsens, and the natural environment degrades further. And it, like many other California cities, is headed in the right direction. It’s planning on building more housing and has developed a nice light-rail system. The next generation of development will be governed by new policies like Sustainable Communities Strategies, vehicles miles traveled metrics, concern for equity and ecology, and a general awareness and embrace of higher-quality urbanism. Improving a city's streets is a far better way to put a city on the map.

Again, this thing isn’t getting built in our lifetime. But something—many things, in fact—will get built as San Jose’s economy will likely keep booming and its population is expected to surge by another 300,000 in the next two decades. Many other low-density, high-prosperity American cities can expect the same.

The kind of urbanism those people are going to need requires us to keep our feet on the ground and our heads out of the clouds. If we really want a nice tower, we’ll always have Paris.

Click for prior CP&DR coverage of San Jose.

A version of this piece appears on Common Edge Collaborative.

Downtown San Jose photo courtesy of Ben Loomis via Flickr; vintage Light Tower photo courtesy of Saratoga Historical Society and Ninian Reid via Flickr.