A world away from the Gaslamp Quarter and the Hotel del Coronado, eastern San Diego County is often described as California's own outback. Its roughly 3,600 square miles of unincorporated county territory encompasses mountains, farmland, and deserts � and includes only 16% of the county's 3 million residents. For the past 12 years, county officials and stakeholders have been trying to decide how to marry an ardently rural area with 21st century planning principles.

Now, after countless hearings and an estimated 500 stakeholder meetings, a general plan update for unincorporated San Diego County will soon be voted on by county supervisors. A vote was expected as early as October, but the number of requests to speak before the supervisors overwhelmed the agenda. Public hearings have been continued to the Dec. 8 meeting, and a vote will likely take place no sooner than January.

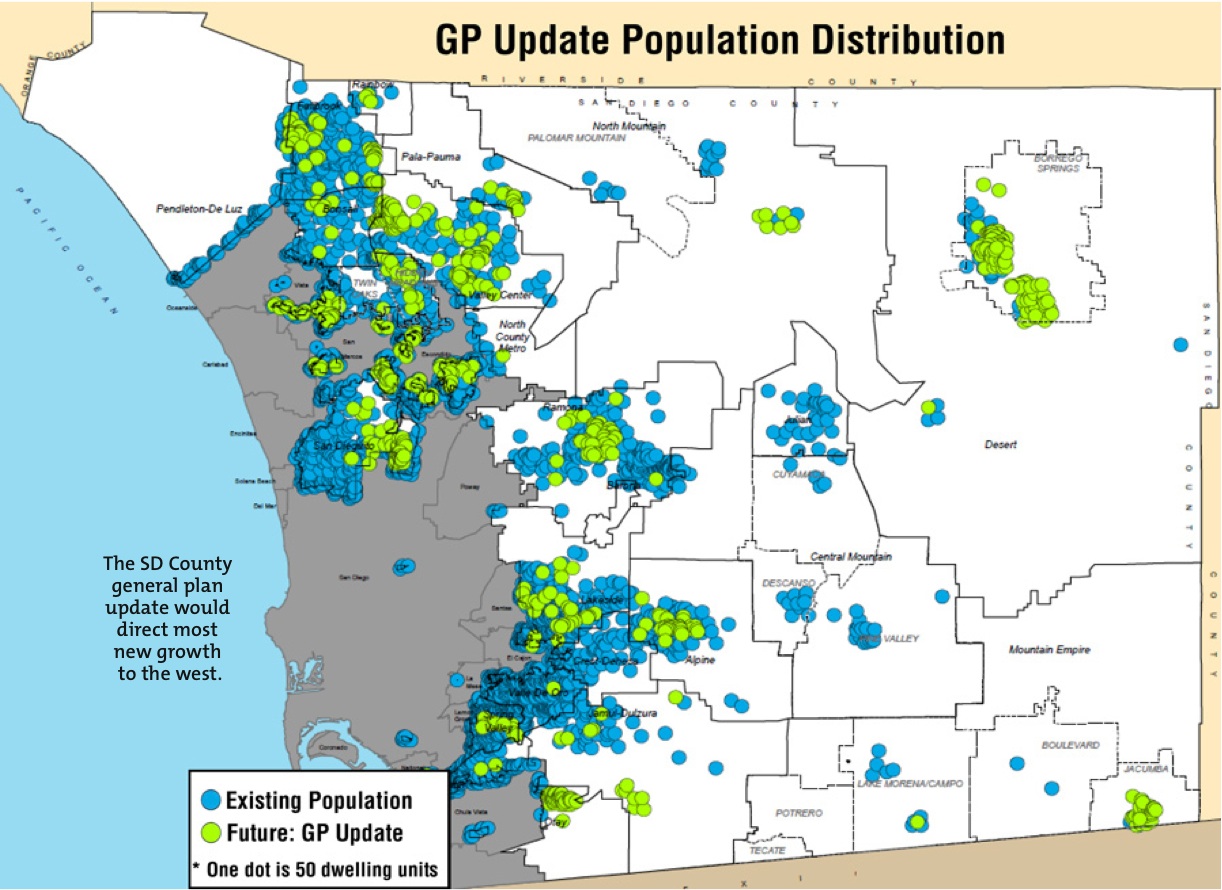

The plan update relies on growth projections by the San Diego Association of Governments, which expects the county's unincorporated areas to grow to from 443,000 to 627,000 residents by 2050. To accommodate that growth, the plan would discourage development in the county's eastern reaches and instead concentrate it in roughly 30% of the county's unincorporated territory. Meanwhile, it would protect up to 393,000 acres of sensitive habitat from development.

Most of the territory designated for higher densities lies in the western portion of the county, hugging inland boundaries of the county's coastal cities. The plan encourages greater density around the county's existing villages � such as Fallbrook, Julian, and Ramona � but strives to keep the backcountry nearly as rural as ever in part through minimum densities and conservation subdivisions.

If the current version is adopted it will be considered a victory for environmentalists and smart-growth advocates, especially those who see San Diego County as microcosm for the rest of the state.

"It's a plan of statewide significance, because San Diego has important natural resources, important farmland, and it has countryside," said Dan Silver, executive director of the Endangered Habitats League and member of the General Plan Interest Group. "This is a watershed for smart growth and good planning. San Diego is a county that has not really either in the past committed itself to smart growth pattern of development or to complete destruction either � it's been kind of an in-between county."

"In-between" does not, however, mean that the county has reached a harmonious balance. Many residents of the backcountry remain concerned that the cosmopolitan forces in the county are imposing a plan that will be too restrictive. A white paper entitled "Fixing the Fatal Flaws" was published in August by a coalition of agricultural and business groups concerned about downzoning and the relationship between the general plan and the community plans. And many of the speakers at those 500 stakeholder meetings have been landowners who are furious about the changes that the plan portends.

The white paper contends that "large swaths of the County are proposed for severe downzoning, a downzoning that is arbitrary and excessive and will result in regressive economic impacts to rural communities."

The challenge of striking the right balance is one reason why the process has taken longer than a decade. Another is its radical departure from the existing general plan, which was adopted in 1978. Now considered legally deficient, the 1978 plan promotes what Silver described as "checkerboard" development, and pays relatively little heed to crucial constraints such as roads, water, sewage service, and the area's considerable environmental resources.

Critics say that if the general plan update is not adopted, any number of inland hamlets could turn into the next Temecula. If projected growth were to occur undirected, Silver estimates that the roads alone to serve dispersed populations would cost up to $5 billion over 40 years.

"It was important to do that because the current general plan from the late 1970s is a complete disaster," said Silver. "It maximizes fire risk, depletes groundwater, maximizes infrastructure costs and greenhouse gas emissions."

"Update" is thus a loose term for a plan that essentially wipes out the old one.

"We decided to use new land-use designations," said Devon Muto, the county's chief of advanced planning. "We're not even using the old terminology. That requires us to re-map the entire unincorporated area. We're not changing density on 70% of our parcels. 10% will increase density, 20% will decrease."

The three general designations are 1) rural, which will include one unit per 20-80 acres; 2) semi-rural with one unit to 0.5 -20 acres; and 3) village, with up to 30 units per acre. Those densities would put the unincorporated county in line with other coastal counties. For comparison, the general plans of Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo counties include densities as low as one unit to 320 acres, while the least dense areas of Los Angeles and Orange County are prescribed for one unit to 40 acres.

"Backcountry development is something they want to move away from an infrastructure perspective�services are not there," said San Diego County Planning Commissioner Bryan Woods. "Good planning says you plan where infrastructure is already developed, and that's where San Diego County is going."

San Diego County planning staff produced a Draft General Plan Map representing these designations several years ago. However, landowners demanded the production of a Referral Map, which treats individual parcels differently according to landowners' individual concerns.

San Diego County planning staff produced a Draft General Plan Map representing these designations several years ago. However, landowners demanded the production of a Referral Map, which treats individual parcels differently according to landowners' individual concerns.

The new plan also establishes a system of conservation subdivisions. That system would discourage the division of properties into larger, dispersed parcels and would instead set aside a relatively large parcel for conservation while creating smaller, clustered parcels for development.

Unlike in many California land use battles, stakeholders are not arguing over environmental protection. Silver said that environmental groups are happy with how the plan addresses ecological resources, and Woods said, "I don't even think that's an issue."

This downzoning has raised inland residents' ire not because of its effects on the environment but rather because of its potential economic impacts. Group such as the San Diego County Farm Bureau contend not necessarily that the new density limits would thwart future developers but rather that they could decimate values of existing farms. Farmers claim that their assessed values are based on the provisions of the current general plan and that a radical departure would rob them of equity.

"Like it or not, the value of land in San Diego County is in large part driven by how you can divided it up and sell it as residential lots," said Eric Larson, executive director of the San Diego County Farm Bureau. "We've been asking since Day One for an equity program, which would be a means of compensating the famers if there is a real loss of value of their land."

The Board of Supervisors may yet explore such a mechanism. As well, some farmers may be compensated for setting aside habitat through the plan's Purchasing Agricultural Conservation Easements program. However, planners caution that these landowners may be overestimating the value of their land. The county commissioned a study by Keyser-Marston Assoc. that found that the downzoning would have a negligible effect on the value of individual parcels.

And just because they can develop their land without constraints does not mean that the demand for such development exists � or that the opportunity would be available to more than a handful of landowners.

"I sympathize with those in the backcountry that feel that they're losing their development potential," said Woods. "But on the other hand I don't think they had what they thought they had from the beginning."

Moreover, this loss of value may not in and of itself warrant compensation � nor is it necessarily planners' concern.

"Ultimately it's up to the Board of Supervisors as to whether they want to try to compensate those land owners," said Muto. "When we up-zone people and they receive a benefit, we don't really ask for things back. It's the same when you look at downzoning. Ultimately, it's a policy decision."

On the macroeconomic scale, the San Diego County Regional Chamber of Commerce has voiced concerns that the plan could hurt the entire county's economy. The chamber contends that the plan's housing element will never be realized, in part because communities will resist the densities that the plan calls for. Moreover, they contend that the plan assumes an unrealistically high per-unit density.

As a result, they say that the county's workforce will be stifled and regional businesses will suffer for lack of employees.

"I don't have confidence that that density is actually achievable," said Donna Jones, vice chair of the San Diego Regional Chamber of Commerce Public Policy Committee.

Muto rejects this interpretation of the plan, noting that current densities in unincorporated communities are 2.92 persons per unit and that the projections are for a modest increase, to 3.02 persons per unit.

"The general plan update provides sufficient housing to accommodate growth beyond 2050," said Muto. "That's a 40-year timeframe and more capacity than most general plans provide. During this timeframe, the unincorporated county would grow at 41.7%, which is higher than the entire region, which would grow at 40.0%."

The Chamber of Commerce and other groups behind the August white paper are also concerned about how the plan treats the county's villages. Stakeholders have demanded the chance to maintain control over the character of their respective communities. Critics worry that that wording in the general plan update is so weak � referring to language that "encourages" certain densities rather than "ensures" them � that community plans could end up superseding the general plan.

County officials question that characterization.

"They can't really supersede the general plan," said Woods. "But they specifically can define parts of the general plan relative to their community character."

Moreover, Muto said that giving communities flexibility and a certain degree of discretion is crucial for the plan's viability.

"Having the communities' plans be able to provide this additional level of direction on how policies are implemented is very important especially given the size of our jurisdiction and how diverse our individual communities are," said Muto. "It's impossible to have a one-size-fits all policy for a jurisdiction like ours."

Contacts & Resources

San Diego County General Plan Update (Official Website)

Donna Jones, Vice Chair, San Diego Regional Chamber of Commerce Public Policy Committee, 619.544.1300

Eric Larson, Executive Director, San Diego County Farm Bureau, 760.745.3023

Devon Muto, Chief of Advanced Planning, County of San Diego Department of Planning and Land, 858.694.2960

Dan Silver, Executive Director, Endangered Habitats League, 213.804.2750