Of the dozens of Grateful Dead songs that have been autoplaying in my head since the news of Bob Weir’s passing broke this Saturday, “Shakedown Street” has been in particularly heavy rotation. The bassline helps, but so does its commentary about American urbanism.

The Dead’s landscapes rarely involved cities. Dead songs are vivid: fairy tales set in the real world, though its landscapes are more pastoral than urban. In “Truckin’,” we pass through the likes of Dallas, Houston, New Orleans, and Buffalo — but we end up at “home.” In “Friend of the Devil,” we “set out from Reno” only to wind up in points unknown.

These landscapes illustrate the Dead’s greatest thematic virtues: their uncanny grasp of Americana. With assists from lyricists including Robert Hunter and John Perry Barlow, the Dead sing of farmers, miners, outlaws, lovers, sailors, truckers, guitar pickers, criminals, innocents, prophets, and mortals. These characters danced, sang, schemed, and slipped away from sea to shining sea: in small towns, open spaces, celestial planes, trails, roads, rivers, and seashores.

“Shakedown Street” takes a surprising detour amid the long, strange trip.

Released in 1978, and performed live 164 times by the Grateful Dead (and many more by its successors, including Dead & Co.), it captures the demise of American cities as vividly as anything else I can imagine from that period. It’s Taxi Driver, Midnight Cowboy, Andy Warhol, Dirty Harry, and Richard Roundtree. It’s Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter, the gas crisis, and the Zodiac killer. Fans in 1978 would have easily recognized all of these urban ills, many of them caused, in large part, by awful post-World War II policies that eviscerated cities from the inside out.

Compared to the rest of the Dead canon, “Shakedown Street” is darker — which is saying a lot for the band whose symbol is a skull — and it feels less ethereal and more of-the-moment.

The Summer of Love was long gone by that time, and a malaise had come over the country, its cities, and music itself. By then, there’s “nothin' shakin’” in what “used to be the heart of town.” Even basic physics has turned against America: “the sunny side of the street is dark.” Jane Jacobs couldn’t have said it better herself. It’s their most urban sounding song, more funk and disco than country, blues, bluegrass, or rock. More Studio 54 than Woodstock.

The city of the Dead is neither Heaven nor Hell — it’s both. Like pretty much everything else in America and everything else in the Dead canon.

Dead songs capture the ambiguities and contradictions of American life like none other, equally aware of hippie idealism and the strong arm of The Man. They express reverence for what America can be and bemusement for what it purports to be: a place where “every silver lining’s got a touch of grey.” The band itself, in its various incarnations and endlessly renewing audiences, lived those ambiguities exquisitely: living hard and singing softly night after night, decade after decade.

The anomaly of “Shakedown Street” is surprising given that the Dead are a thoroughly urban creation. Most bands are, of course. Cities bring together creative, multitalented people. But, whereas the bands of Los Angeles or New York consist of newcomers who step off the bus and find their people, the Dead were home-grown in San Francisco. The scene and the city were intertwined, and they were public.

The Dead’s 2,000-plus shows took them well beyond California, to venues as urban as Madison Square Garden and as rural as The Gorge Amphitheater in Washington State. There’s nothing necessarily special about that — plenty of big acts play big venues. But, of course, the Dead’s city traveled with them. Forming, reforming, and morphing at every leg, the extended Deadhead tribe exemplifies two of America’s greatest distinctions: the privilege of mobility and the yearning for community.

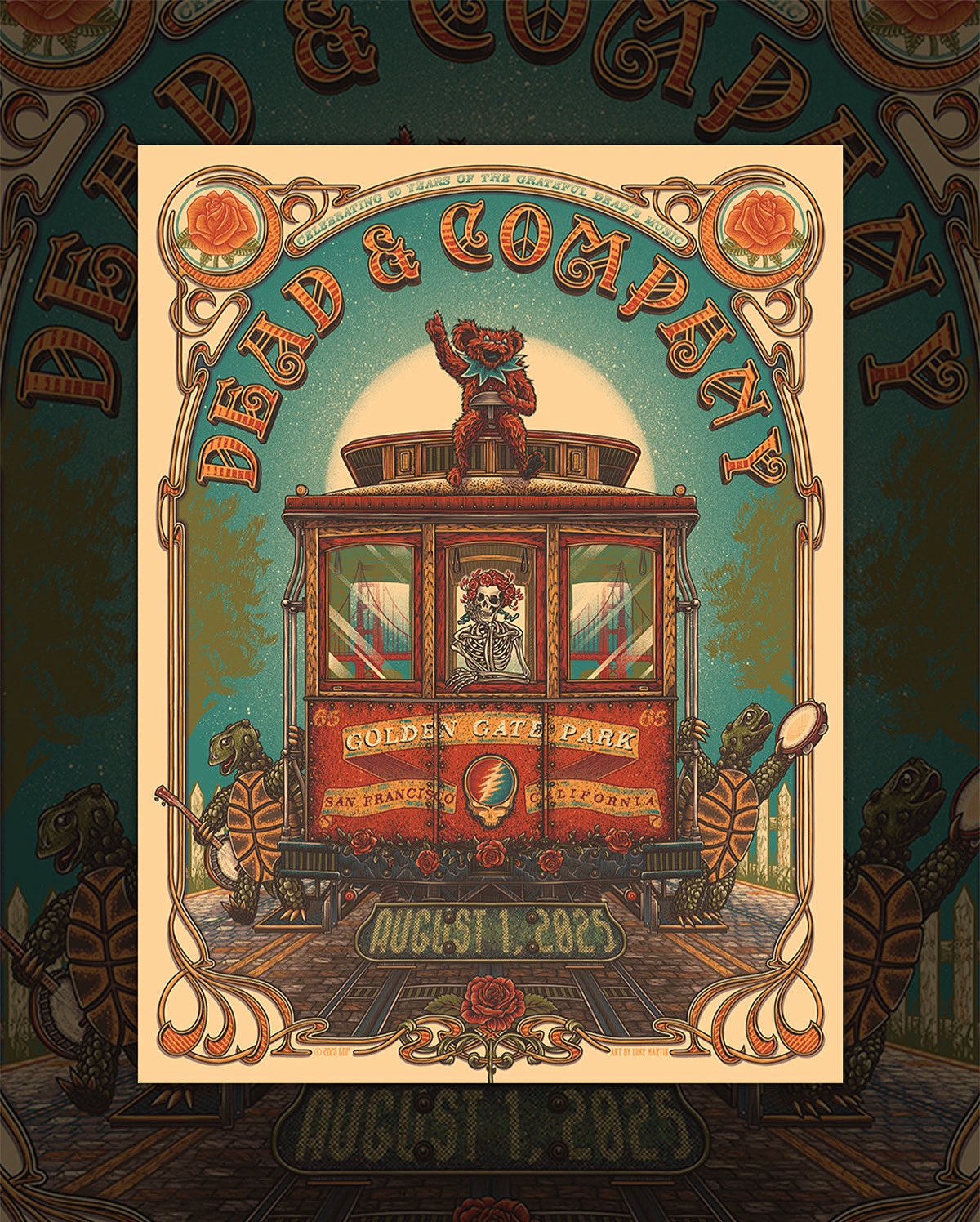

That’s one of many reasons for their resurgence. I hardly need to recount all the forces that have alienated Americans from each other these days: social media; politics; tribalism; covid; and, not insignificantly, urban stagnation and, especially, cost of living. “Bowling alone,” to invoke Robert Putnam, was the least of it. Dead & Co. shows brought people together, just as their predecessors had for decades. Most recently, they went back to their roots with a series of three shows in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, a venue rivaled for urban congregation only by New York’s Central Park and Chicago’s Millennium Park. It turned out to be Bobby’s final farewell.

Whatever the location, the band evoked happier times — albeit idealized — when hippies could hang out on stoops and streetcorners, play some music, twirl around, and imagine a better world. All while making rent, without a tech founder or stock option in sight.

The Dead even managed to soften our least-urban city, holding down residencies at the Sphere in Las Vegas. Its most spectacular effect was nothing if not a celebration of urbanism. A life-size recreation of 710 Ashbury Street pulls back into an aerial of San Francisco, then the entire Bay Area, the state, and eventually, into outer space, from which their stalwart frontman now looks down upon us.

The ‘60s are officially over. For American cities, and California cities, that’s probably a good thing. They have bounced back mightily from their “Shakedown” era trough. Today’s San Francisco remains remarkable, but it’s entirely possible that the cost of living means that it will never again be built on rock n’ roll. I just hope that, someday, they can rekindle at least a few aspects of the Dead’s heyday, back when kids envisioned a new world and old folks were the squares (how times have changed).

To state the obvious: a counterculture cannot be planned. But the conditions to nurture creativity, novelty, optimism, and fellowship most certainly can. You don’t need a miracle. You need affordability, equity, density, walkability, openness, and, yes, a little bit of fairy dust. You might need righteous causes to support and Establishments to rage against, which are in woefully ample supply today. You need freedom, and you need some love--for art, music, and one another.

Bobby Weir may be gone, but don't tell me these towns ain't got no heart. We all gotta poke around.

Images: Dead & Company via X.