CAMBRIDGE, Mass. -- Angelenos of a certain age may remember Allan Malamud, whose column in the Herald-Examiner, and later the Los Angeles Times, was called “Notes on a Scorecard.” He jotted down scattered thoughts and observations—some amusing, some profound—over the course of nine innings and shared them with readers.

I recently attended the annual journalists forum at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, which entailed two days of discussion on all things land use around the country. Based on panels, keynotes, and side conversations, here are a few notes on the proverbial tract map.

* * *

A reporter from the East Coast asked me what the one-year anniversary story on the Los Angeles fires will be.

At first, I said there was no story. Almost nothing has broken ground yet, and no vision for Pacific Palisades (in the City of Los Angeles) or Altadena (in unincorporated Los Angeles County) has been announced or adopted. The sniping about whose fault it is—Mayor Karen Bass, Gov. Gavin Newsom, the LAFD, or Prometheus himself—will probably persist forever. (Rarely discussed: the inherent dangers of developing and living alongside an eminently flammable, drought-prone landscape.)

The real story centers on decisions: What have homeowners, 12 months into exile, decided to do? What can they afford to do? Rebuild and move back? Rebuild and sell? Cut their losses? Go bankrupt buying insurance?

* * *

The federal government has clawed back $80 million in funding for wildlife corridors nationwide to help various fauna move about their habitats in the face of incursions by roads, development, and other uses. I couldn’t help doing the math: that’s exactly $12 million less than the cost of the soon-to-be-finished Wallis Annenberg Crossing near Calabasas, in western Los Angeles County.

Over 150,000 people will drive under the crossing every day, so hopefully that outsized investment will be good PR. Otherwise, as much as Los Angeles loves its mountain lions, it sounds like a lot of money to help a few cats on the prowl.

* * *

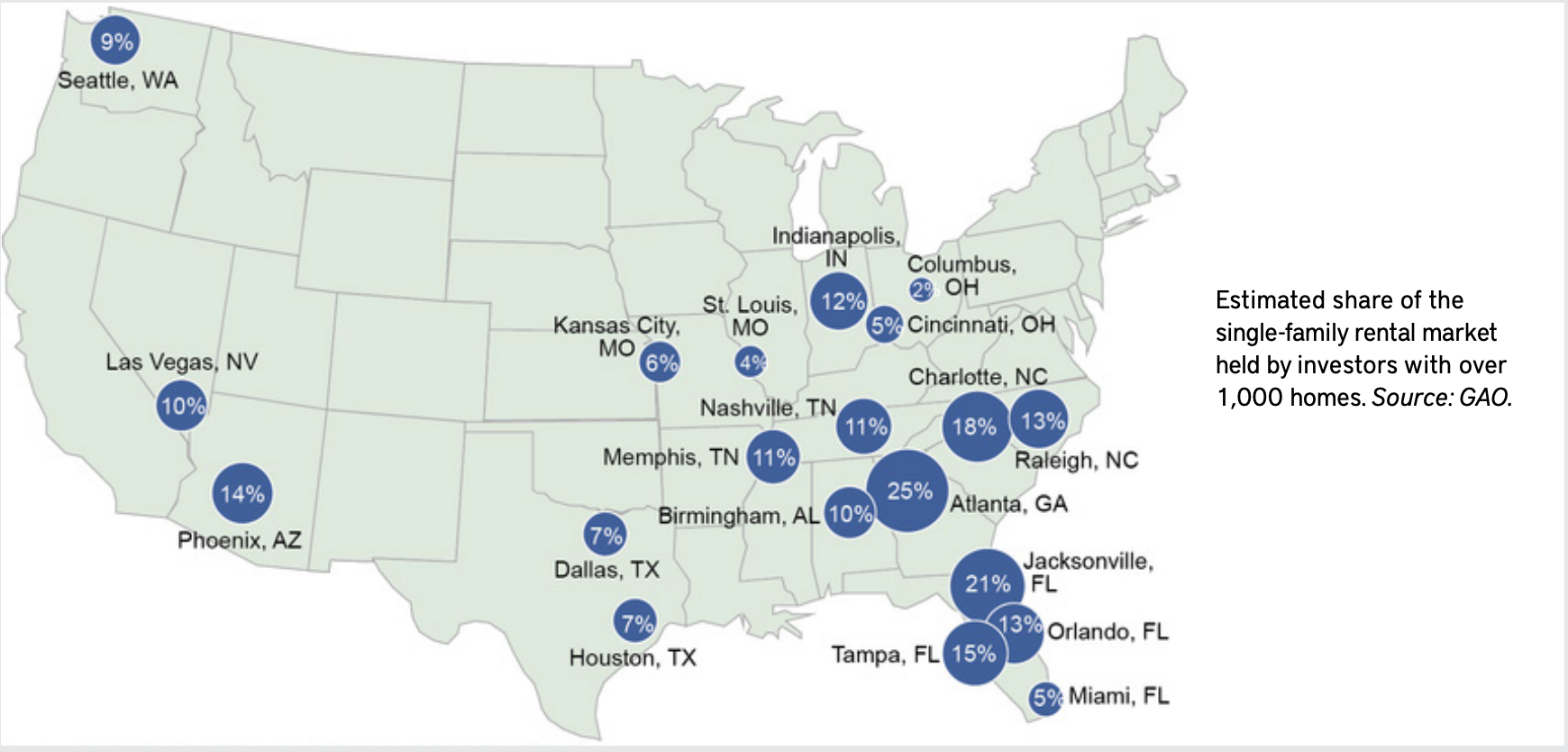

The Lincoln Institute has undertaken an impressive study to identify the owners of every single residential parcel in the United States, called “Who Owns America?” to discern, in part, how much real estate has been purchased by corporate entities.

I was not previously convinced that the specter of corporate ownership wasn't overblown. I was wrong. In some cities, corporations own up to 20% of the housing stock (St. Louis and Baltimore among them), disproportionately located in low-income and minority-majority neighborhoods.

Importantly, corporate investors tend to overpay by 4%, meaning they push up prices for everyone.

California appears relatively unscathed. For once, our high costs work in our favor: real estate is too expensive for capitalist speculators to take a risk.

* * *

An interlude with Providence, Rhode Island:

Providence, RI, Mayor Brett Smiley took a question about his measured approach to bike lanes, which has disappointed many bike advocates in Providence. He argued that the development of bike lanes should be commensurate with use: currently less than 10% in Providence, and almost 0% at certain times of year. (Smiley has recently been in the news for far sadder reasons.)

Even allowing for induced demand, investment in bike lanes has to be sensible and strategic.

I think everyone in California can name a newly installed bike lane that is both controversial and under-utilized. A lane on Venice Blvd. basically sunk the career of an L.A. City Council member a few years ago, and I’m really not sure that permanently shutting down all of San Francisco’s Great Highway is such a good idea.

Bike advocates should lobby as hard for biking—to help other people adopt biking and use those lanes—as they do for the lanes themselves.

Providence puts California to shame in an unexpected way. The city has declared itself a “city of design,” partly because of the Rhode Island School of Design and partly because it’s converting old mill buildings into inexpensive live-work spaces.

Thus, Providence’s creative economy is on the rise at the very moment when Los Angeles’ is being sold off for parts (cf. Netflix’s intended acquisition of Warner Bros., announced recently).

With the exception of former Mayor John Bauters of Emeryville, I don’t think I’ve heard a mayor in California speak as enthusiastically about development as Mayor Smiley of Providence did.

Rather than speak in hushed tones about “fair shares,” “following guidelines,” and “upzoning in appropriate places,” Smiley said, “People can choose where to live. We want them to choose Providence.” Full stop.

So, California, what do we want?

* * *

Our keynote speaker was Michael Sandel, Harvard professor of political philosophy and teacher of the near-legendary course “Justice.” I asked him whether cities should be obligated—as a moral principle—to accommodate any and all people who would like to live in them.

Sandel did not declare a categorical obligation, but he posited that if a city was to acknowledge such an obligation, it should also adopt a land-value tax, echoing 19th-century economist Henry George. Sandel reasoned that speculation in real estate leads to scarcity whereas a land-value tax promotes development and is infinitely expandable to match revenue with demand for services.

That recommendation was gratifying to the Georgists in the room. The institute’s founder, George C. Lincoln, was an enthusiastic Georgist, as are many current staff members.

(Side note: Sandel forbids screens in his classrooms. That strikes me as a pedagogically sound policy as well as an inherently pro-urban policy, insofar as human connection is one of the purposes of cities.)

* * *

“States should set housing targets and enforce them.”

With apologies to Huntington Beach, California is doing at least one thing right.

* * *

Lincoln Institute President George McCarthy, an expert in local tax policy, mentioned that, for a while, Bogotá, Colombia, invited residents to voluntarily add to their tax payments if they wanted to support the city.

On its face, this sounds insane. Who would voluntarily pay a tax? But let’s face it: most cities are not as nice as residents want them to be, and some people understand that a desire without a commensurate willingness to pay is tantamount to whining.

There’s no better place than California to experiment with this approach. Why? Prop. 13 ensures that many Californians pay a fraction of their fair share. I’d like to think that at least a few of them would recognize their good fortune clearly enough to chip in.

My proposal: whatever bonus a homeowner adds to his or her tax payment, half should be spent in the immediate neighborhood and half should be pooled and allocated to underserved communities. Dare I call it a win-win-win?

* * *

Here’s something I didn’t know: A “Corruption tax” is a premium imposed by lenders on localities that do not have robust press coverage.

What does press coverage have to do with lending liability? Lenders know that the absence of a civic watchdog makes their investment more precarious than it would otherwise be. So, developers, support your local newspapers! (Even if they annoy you sometimes.)

* * *

For every local mayor and councilmember who is incensed over preemptive pro-housing legislation from Sacramento, they are in good company in almost every state in the country.

This chart, compiled by the Mercatus Center, indicates around 400 total housing bills. These bills represent 33 states, according to the Mercatus data.

That’s a torrent of bills, for sure. But by our count, at least 200 of those bills are from Sacramento, in pretty much all 13 categories.

* * *

A ballot measure to reduce local taxes or otherwise alter a locality’s revenue model “is only one half of a conversation” and therefore perilous, at least compared to legislation. “At least legislators have to think about other arguments. Ballot measures don’t need balance.”

This is, of course, how you end up with measures like Los Angeles’s Measure ULA transfer tax.

* * *

One discussion focused on state preemption of local land-use control, which is basically the story of California for the better part of the past decade. Cities have understandably carped about unfunded mandates and the burden that new housing places on them—with dubious fiscal benefits.

Speakers had two major recommendations: 1) provide funds for planning; and 2) link intergovernmental transfers (i.e., funds the state sends to cities) to the production of housing: “Until growth is a promise that common pool resources will be invested in where growth is happening, we are never going to be able to solve the housing crisis.”